Brain Bites

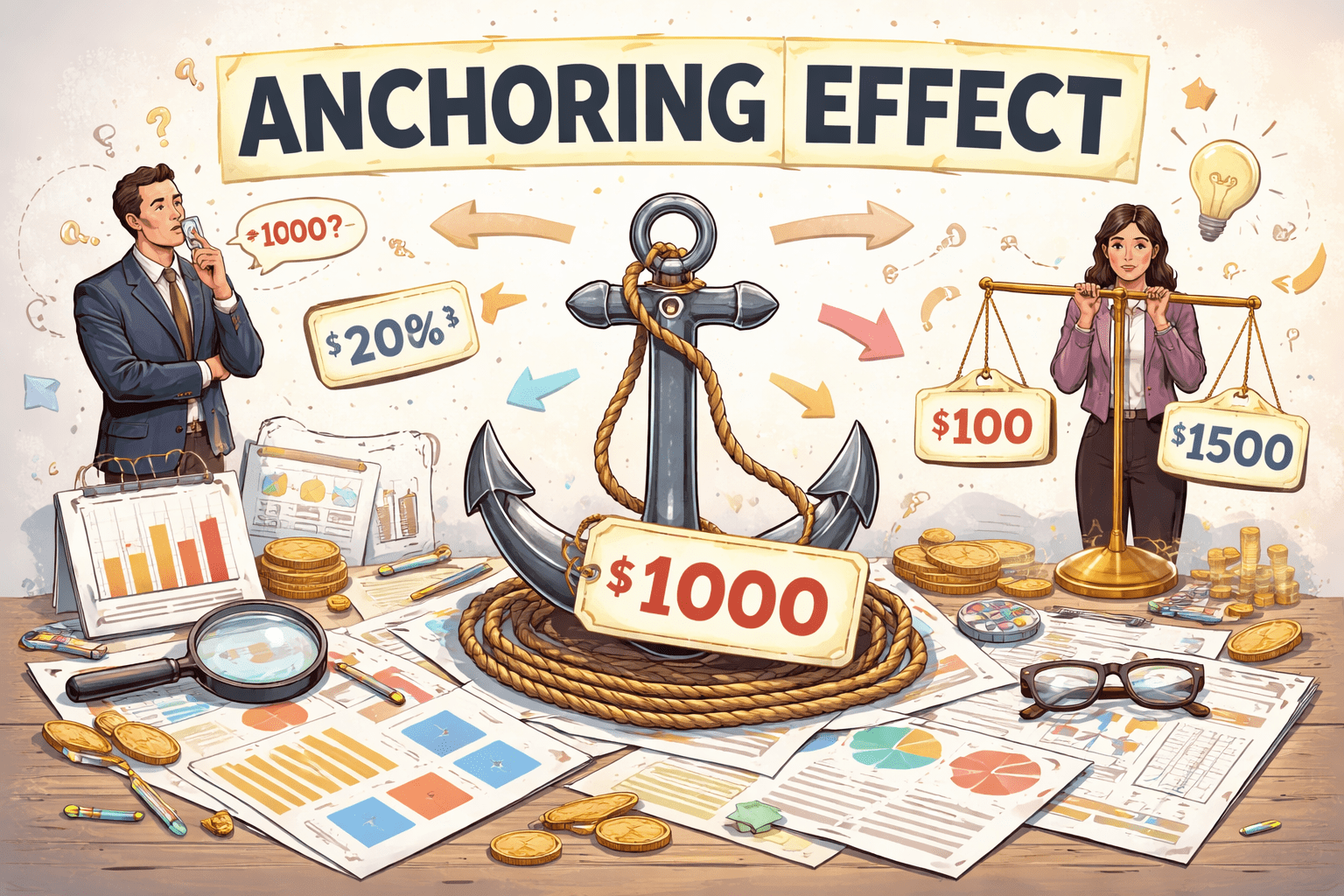

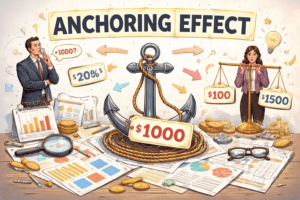

The Anchoring Effect

What is it and how does it work?

The concept of anchoring was first introduced by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s. Their groundbreaking research laid the foundation for our modern understanding of cognitive biases in judgment and decision-making. At its core, the anchoring effect describes our tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we encounter when making decisions. Once an anchor is set, subsequent judgments are made by adjusting away from that initial value. Crucially, these adjustments are usually insufficient, creating a systematic bias toward the original anchor. The anchor becomes a reference point, shaping estimates, evaluations, and choices, even when it is arbitrary, misleading, or clearly irrelevant to the decision at hand.

Put simply, the brain latches onto the first number or piece of information it sees and struggles to move far away from it—even when logic says it should. The anchor functions much like a physical anchor tied to a boat: the boat can drift slightly, but it remains constrained by where the anchor rests. As a result, even random or absurd starting points can exert a powerful pull on later judgments, decisions, and emotional reactions.

Consider a common example. Imagine you are shopping for a new phone. The first model you see is priced at $1,200. A few minutes later, you notice a nearly identical phone—perhaps only a different color—priced at $800. Suddenly, $800 feels like a bargain. Yet this sense of value exists largely because your perception was anchored by the initial $1,200 price. If that first number was intentionally inflated, its primary purpose may not have been to sell the expensive phone at all, but to make the second one seem reasonable by comparison. This is anchoring in action.

How does it influence your life?

The anchoring effect silently shapes countless decisions you make daily. Here are some of the examples of how our lives are being influenced by it every day:

“Original Price” vs. “Sale Price” in stores and online

- You see: “Was $299 — Now $149”

- Your brain anchors on the $299.

- $149 suddenly feels like an amazing deal, even if the item was never actually sold for $299 (or was only listed at $299 for a few hours to create the anchor).

- This is one of the most powerful and widespread uses of anchoring in retail. Studies show people are willing to pay significantly more when they first see a high “reference” price.

Restaurant/hotel menu design

- They put the most expensive item first (e.g., $98 steak at the top).

- Suddenly, the $42 chicken or $58 pasta feels reasonably priced.

- Without the $98 anchor, you might have thought $58 was expensive.

- Same trick on wine lists: expensive bottle listed first makes mid-range bottles seem like good value.

Real-estate listing prices

- House listed at $749,900 (instead of $750,000).

- Buyers anchor on the “under $750k” feeling and perceive it as cheaper than similar homes listed at $775,000.

- Agents often suggest slightly absurdly high listing prices, knowing buyers will negotiate down, but the high starting point anchors the final sale price higher.

Car dealerships – “Your trade-in value”

- Dealer says: “We can give you $12,000 for your old car.”

- You were hoping for $15,000–$16,000, but now $13,000–$14,000 starts to feel fair.

- They anchor low on purpose so even a small increase feels like they’re being generous.

News headlines and social media posts

- “Experts warn inflation could hit 8% next year”

- Even if later experts say 3–4%, many people’s mental forecast stays anchored closer to 8%.

- The first big/scary number they read keeps pulling their expectations.

“Suggested tip” percentages on card machines

- Screen shows: 18% — 20% — 25% (or even 30%)

- The first/default option (often 20%) becomes the anchor.

- Many people feel rude choosing below it, so they pick 20% even when they normally tip 15%.

- Some places now start at 20–25% as the lowest visible button deliberately anchoring higher.

“Limited time offer” countdown timers and “Only 3 left!”

- You see: “$79 — was $199 — offer ends in 2 hours!” + countdown timer.

- The high original price + urgency anchors you to think you’re getting a huge discount and must act now.

- Many of these timers reset or are fake — but the anchoring + scarcity combo is extremely powerful.

The first salary number in a job offer

- Employer says: “The salary range for this role is $65,000–$75,000.”

- Even if you were hoping for $90,000+, your negotiation usually starts somewhere near $70,000–$78,000.

- If they had opened with “$90,000–$105,000,” you would likely negotiate toward $95,000+.

- Recruiters and companies know this, that’s why many deliberately state (or hint at) a lower number first.

Charity and donation pages

- “Most people donate $50 / $100 / $250”

- Or preset buttons: $25 – $50 – $100 – $250 – Other

- The first visible amounts become anchors.

- People who see $100–$250 first tend to give significantly more than people who see $5–$10–$25 first.

Subscription pricing tiers

- Basic: $9.99

- Standard: $14.99

- Premium: $24.99

- Most people pick Standard because it’s anchored between the cheap and expensive options — making it feel like the “smart middle choice,” even if they don’t need all the Premium features.

The good news is that you can do something about lowering the probability of its influence. Here are some of the steps you can take to mitigate the Anchoring effect:

- The “Consider-the-Opposite” Strategy is the gold standard in psychological research for fighting bias. When you are presented with a number (like a car price or a salary offer), actively search for reasons why that number is wrong or irrelevant. An example of this is when a salesperson says a watch is worth $500, immediately list three reasons why it might only be worth $100 (e.g., cheaper materials, older model, competitors’ prices). By forcing your brain to retrieve inconsistent information, you break the “selective accessibility” that the anchor relies on.

Set Your Own Anchors First is a strategy used in negotiations. The person who speaks first often wins. If you walk into a meeting with a firm, research-backed number already in your head, you create your own “internal anchor.” When you are a buyer, do the “Pre-emptive Strike” and make the first offer. This forces the other party to adjust relative to your number rather than the other way around.

Use “System 2” Thinking and just slow down. Anchoring thrives on split-second decisions and emotional pressure. Delay the decision, and if a deal is “only available for the next 10 minutes,” that’s a red flag. Step away, grab a coffee, and look at the data in a different environment. One approach is also to generate multiple estimates. Don’t just settle on one “fair price.” Create a range (the “Low, Medium, High” approach). This prevents a single point from becoming a trap.

Expert Knowledge and Objective Data will help you out with resisting any anchors the opposite site might “throw at you”. So, before any big purchases, be sure to research beforehand, and if you know the market value of a house is $400k based on 20 recent sales, a seller’s “dream price” of $600k will feel like a joke rather than a starting point. Ignore the “List Price”. In retail, look at the final price and ignore the “original price” or “percent off.” One thing that always helps is if you ask yourself, “Would I buy this for $50 if it weren’t on sale?”

5. The “Walk Away” Point is a tactic where you know exactly when you will walk away from a purchase of a deal. That creates a hard boundary that anchors cannot pull you past.

Experiments done on this subject

Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974)

This is the original formal experiment documenting the anchoring effect in judgment and decision-making.

How was it done:

Participants watched a “Wheel of Fortune” spin. The wheel was rigged to land on either 10 or 65. Immediately after, participants were asked two questions. “Is the percentage of African nations in the UN higher or lower than the number you just saw?” And the second one was “What is your exact estimate of that percentage?”

Findings:

Those who saw the low anchor gave significantly lower estimates, and those with high anchors gave higher estimates, despite the wheel being random. This showed that even random numbers influence judgments.

Real-world application:

This experimental design underlies much of behavioral economics and shows how irrelevant numbers (list price, suggested salary, past data) have an effect on our judgments in everyday contexts like pricing, negotiation, and forecasting.

Multiplication Problem – 8! vs. 1×2×… (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974)

A demonstration of self-generated anchoring created by the order in which numbers are presented.

How was it done:

High-school students had only 5 seconds to estimate the product of eight numbers. One group saw the descending sequence (8 × 7 × 6 × 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1); the other saw the ascending sequence (1 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 5 × 6 × 7 × 8).

Findings:

Estimates were biased toward the starting point. Those starting low gave lower estimates, their median estimate was 512, while those starting high gave higher estimates, and their median estimate was 2250. The correct answer is 40,320.

Real-world application:

This shows anchoring can occur even without explicit numeric anchors and that internal thought patterns can serve as anchors, influencing complex estimation tasks.

Social Security Numbers and Willingness-to-Pay (Ariely, Loewenstein & Prelec, 2003)

A series of experiments testing how arbitrary anchors influence people’s valuations of goods.

How was it done:

MIT students first wrote the last two digits of their Social Security Number. They were then asked whether they would pay that dollar amount for six ordinary products (e.g., a wireless keyboard, a wine, a chocolate, a book). Finally, they stated their maximum willingness to pay for each item.

Findings:

Students with SSN endings 80–99 bid 216–346% higher than those with 00–19. Higher random numbers correlated with higher willingness to pay, even though the number was irrelevant to value. Despite the bids adjusting coherently, they remained influenced by arbitrary anchors.

Real-world application:

Charity suggested donation amounts, auction starting bids, real-estate listing prices, and personal budgeting (the first price you see becomes your reference), even if it is not connected to the thing you are looking to buy or sell.

Judicial Anchoring — Englich & Mussweiler (2001, 2006)

Anchoring experiments with actual trial judges to test bias in sentencing decisions.

How was it done:

Judges evaluated identical legal cases after being exposed to either a high or low suggested sentence (sometimes even issued by a non-expert or randomly determined).

Findings:

Anchors substantially influenced sentencing outcomes. Highly suggested sentences led to longer actual sentences, even though the underlying case facts were identical.

Real-world application:

Shows anchoring bias can affect high-stakes decisions in the legal system, raising ethical and policy concerns about how sentencing guidelines or prosecutorial demands are framed.

Visual Event Boundaries Eliminate Anchoring (Ongchoco et al., PNAS 2023)

A groundbreaking study showing that walking through a doorway (a natural “event boundary”) can wipe out anchoring.

How was it done:

Participants walked a virtual 3D room in an immersive animation. Some passed through a doorway, others did not. Before the trial, they completed a CAPTCHA-style task that provided a low or high two-digit anchor (presented as irrelevant). They then made unrelated judgments (valuations, factual questions, legal sentences).

Findings:

Without a doorway, the anchoring effect stayed strong. On the other hand, the ones who walked through a doorway, their anchoring disappeared or reversed. The effect held across economic, factual, and legal tasks.

Real-world application:

Be mindful of office design, use doorways as “reset” points. Use the same “tool” for the doorways concept in virtual meetings, therapy techniques, and app designs so you are separating screens to reduce carry-over bias.

Fooled by Facts – Large-Scale Field Experiment (Yasseri & Reher, 2022)

One of the largest real-world tests of anchoring outside the lab, using a popular prediction app.

How was it done:

The experiment was conducted in the “Play the Future” (PTF) mobile app, a free Android/iOS game operational since 2016 with over 300,000 users and about 82,000 monthly active players. Users predict numeric outcomes of real-world events (e.g., weather temperatures, stock prices, flight arrival times) for points, prestige, and occasional prizes, receiving feedback after events resolve. Every day, the app gave players two hints. The first hint was normal background info (same for everyone). The second hint was the “trick” hint, and this is where they secretly changed the number to be either very low or very high (the anchor).

Findings:

The number they showed first really moved people’s guesses. If the hint showed a low number, most people guessed lower, and if the hint showed a high number, most people guessed higher. Even though the number was just one past example, it pulled everyone’s answer toward it. It worked the same for almost everyone. Men and women were equally affected. People who played the game every day (very experienced) were just as influenced as people who played only a few times. People who were usually very accurate at guessing were still pulled by the anchor just as much as people who were usually wrong. And when the hint pretended to be an “expert opinion,” it was even stronger

Real-world application:

When something is labeled “expert forecast”, “Wall Street target”, “our team prediction”, or “AI estimate”, people trust it more and let it pull their thinking harder. And that is true in most aspect in our life. It is true in shopping, when negotiating for a salary, if the employer says the job pays “up to $85,000”, most people will aim around there (or lower). Same in News, social media, and influencers, as soon as an “expert” says something is true, we believe that more than we trust ourselves.